The interference phenomena of light not only demonstrated its wave nature but also inspired humanity to explore the wonders this behaviour revealed.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Light is full of surprises, and one of the most beautiful phenomena it exhibits is interference. A cool and fascinating example is an oil film on water. It displays gorgeous, shifting colour patterns on the surface. Understanding interference is key to grasping how light behaves as a wave.

The Essentials of Wave Interference

Interference occurs when two waves travel in the same medium. Depending on how they meet, the resulting wave can have either of the outcomes:

- A greater amplitude than the individual waves

- lesser amplitude than the individual waves

Based on this, there are two types of interferences.

Types of Interferences

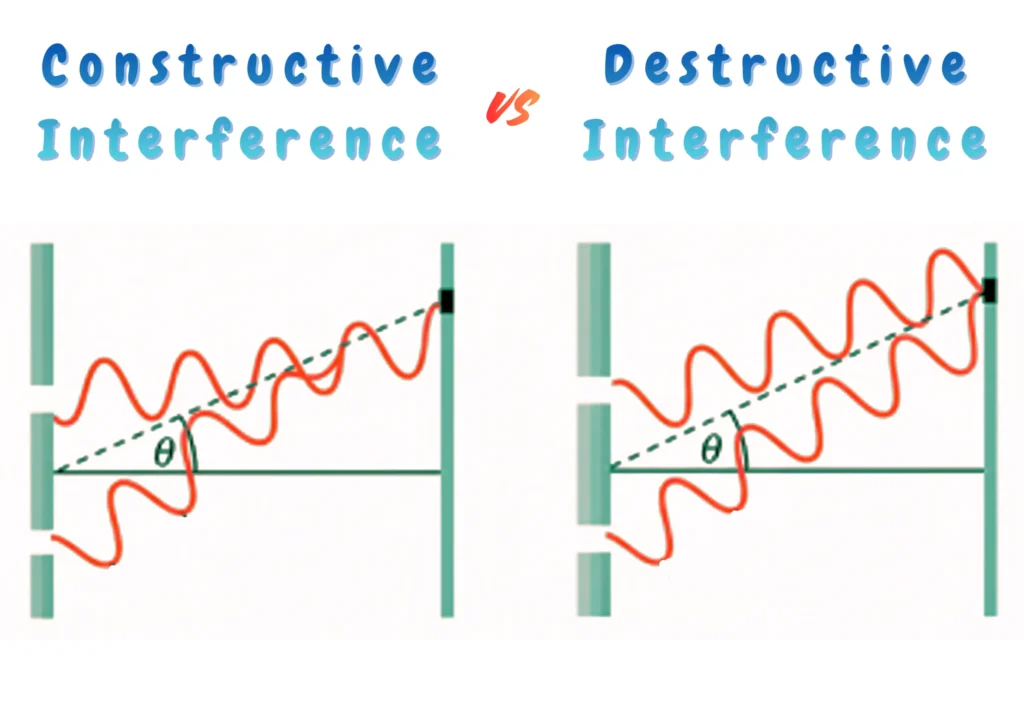

The two types of interference are constructive interference and destructive interference. The difference between the two is as follows:

- Constructive Interference: When waves interfere constructively, the amplitude of the resultant wave is greater than either individual wave. This happens when crests meet crests and troughs meet troughs.

- Destructive Interference: In this case, the amplitude of the resultant wave is less than either individual wave. This occurs when crests meet troughs.

Conditions for Detectable Interference

Interference of light is not easy to observe because the typical light sources emit light randomly. To see the interference of light clearly, two crucial conditions must be met:

Monochromatic Light

A flame test for sodium chloride shows a bright yellow colour (around 589 nm), which is nearly monochromatic (same colour), due to light emitted by sodium atoms.

Coherent Sources

Sources that emit waves of the same frequency and a constant phase difference are called coherent sources.

Young’s Double Slit Experiment

The Famous Proof for Wave Nature of Light.

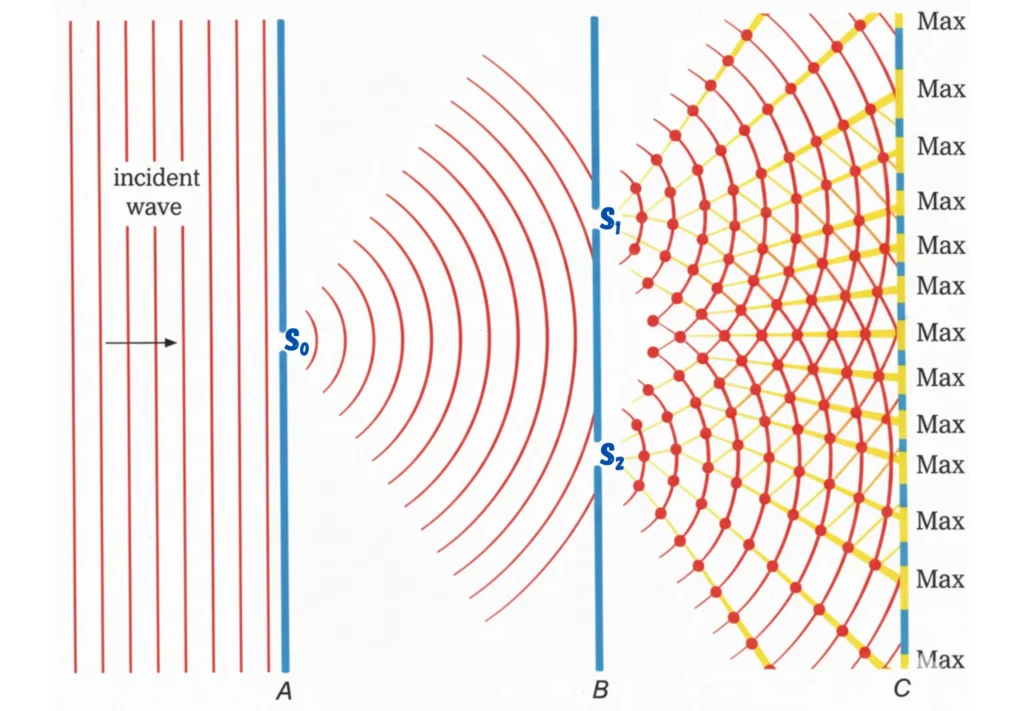

In 1801, Thomas Young devised a classic experiment to study the interference of light. This setup uses a single monochromatic light source to illuminate a screen with two narrow slits.

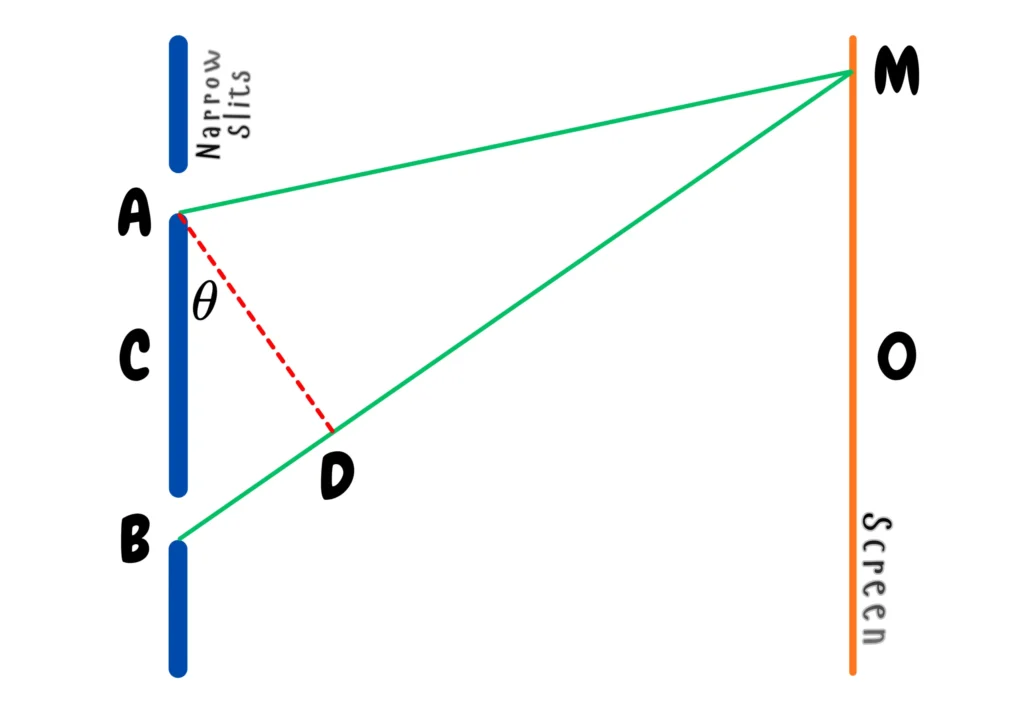

The Setup and Fringe Formation

The slits, illuminated by a single wavefront, act as two coherent sources of secondary wavelets (Huygen’s principle). The superposition of these wavelets produces an interference pattern on a screen placed a distance away.

What are Fringes?

Interference Pattern

Fringes are a series of bright and dark bands that appear on the screen.

- Bright Fringes (Maxima): Formed by constructive interference, where crests meet crests.

- Dark Fringes (Minima): Formed by destructive interference, where crests meet troughs.

Mathematical Conditions

For a given point P on the screen, the outcome (bright or dark) depends on the path difference(BD) between the two waves arriving from the slits.

Path Difference

It is the difference in the distances travelled by the two waves from their respective slits (or sources) to a point on the screen.

The path difference can be expressed in terms of the number of wavelengths contained within ![]() . Additionally;

. Additionally;

![]()

&

![]()

For Bright Fringes (Maxima)

The path difference must be an integral multiple of the wavelength.

![]()

Where ![]() .

.

Also, from the triangle ADB:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Equating (i) and (ii):

![]()

OR

![]()

The central bright fringe occurs at ![]() .

.

For Dark Fringes (Minima)

The path difference must be a half-integral multiple of the wavelength.

![]()

Also,

![]()

Equating (iv) and (v):

![]()

OR

![]()

The first dark fringe, for this case, will occur at ![]() i.e., half the wavelength of the light.

i.e., half the wavelength of the light.

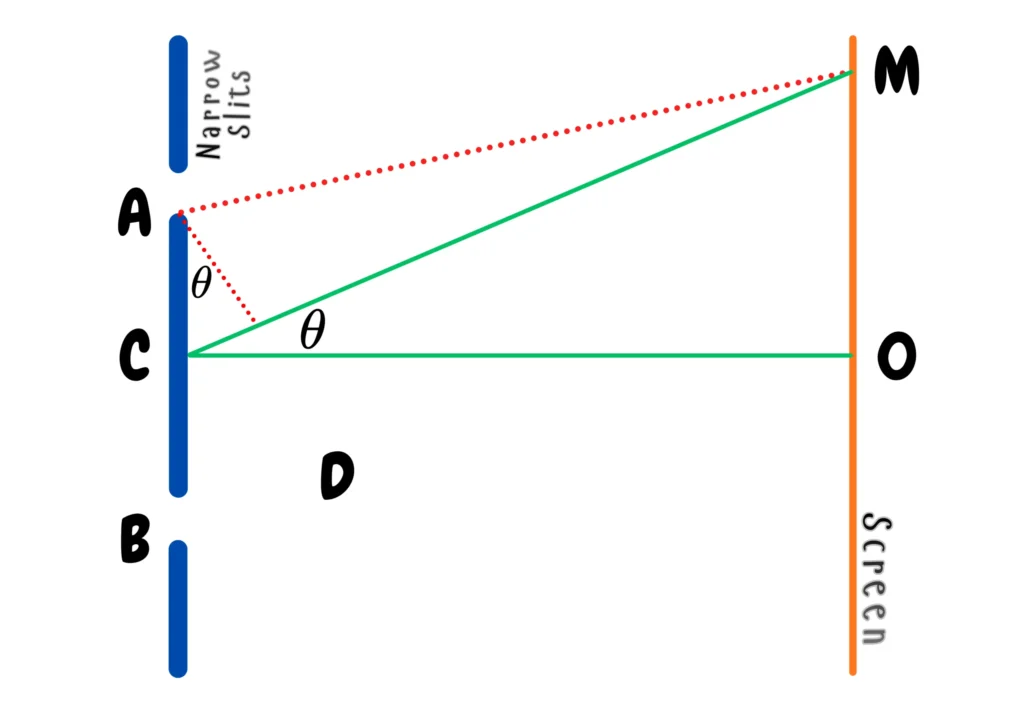

Position of Fringes

The equation for the position of the fringes, both bright and dark, can also be determined from the central point O. For instance, in the triangle COM, as shown in the figure.

distance of fringe from the central point O

distance of fringe from the central point O distance of screen from the source of light (slits)

distance of screen from the source of light (slits)

From trigonometry, you know that for a small angle ![]() ;

;

![]()

![]()

![]()

Replacing the value of ![]() into equations (iii) & (vi) yields the position of the bright and dark fringes, respectively.

into equations (iii) & (vi) yields the position of the bright and dark fringes, respectively.

For Bright Fringe

![]()

![]()

For Dark Fringe

![]()

![]()

Fringe Spacing

The distance between two adjacent bright fringes (or adjacent dark fringes) is called fringe spacing. Let us consider;

Calculation of Fringe Spacing

Let us consider;

The spacing between the two adjacent fringes is calculated as:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Where,

spacing between the two bright fringes

spacing between the two bright fringes

Key Takeaways

- The same equation can be used to find the spacing between two dark fringes or one bright and one dark fringe.

- Crucially, this result shows that bright and dark fringes are of equal width and are equally spaced.

increases with longer wavelengths (e.g., red light).

increases with longer wavelengths (e.g., red light). also increases with greater distance (L) between the slits and the screen.

also increases with greater distance (L) between the slits and the screen. decreases with a greater separation (d) between the slits.

decreases with a greater separation (d) between the slits.- The equation is vital for determining the wavelength of light used in the experiment.

Thin Films, Newton’s Rings, and the Phenomenon of Interference

Interference is not confined to slits alone. The captivating colours that appear in thin, transparent layers of material are also governed by interference.

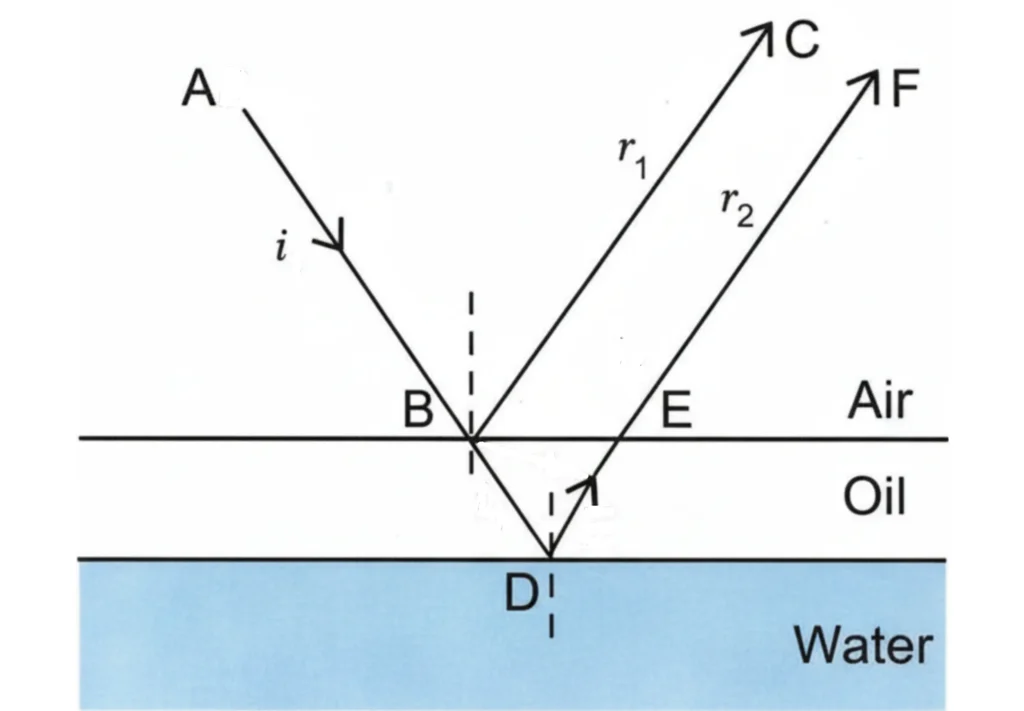

Interference in Thin Films

A thin film is a transparent medium whose thickness is on the order of the wavelength of visible light.

The best examples of the thin film are soap bubbles or oil films.

The Underlying Mechanism

When light strikes the surface of a thin film, the following things happen:

- A part of the beam is reflected from the upper surface

- The remainder is transmitted into the film

- The transmitted part reflects internally before emerging

The two reflected rays remain coherent and thus interfere with each other. They produce the characteristic patterns of constructive and destructive interference.

Note

When reflection occurs from a denser medium (e.g., air to oil), the reflected ray undergoes a phase shift of π radians (half a wavelength). When reflection occurs from a rarer medium (e.g., oil to air), no phase shift occurs.

This phase difference determines whether the interference is constructive or destructive at any point.

White Light and Interference on a Thin Film

When white light falls upon a thin film of varying thickness, each wavelength (or colour) of light interferes independently.

At any given point, if destructive interference occurs for one particular colour, that particular colour is suppressed. However, it produces the other constituent colours of white light. The result is the outstanding array of colours often observed across the surface of the film.

Newton’s Rings

Newton’s rings are a series of concentric bright and dark fringes formed by the interference of light in a thin air film created between a plano-convex lens and a flat glass plate.

Experimental Arrangement

A standard experimental setup looks like this;

- A plano-convex lens is gently placed with its convex surface in contact with a flat glass plate.

- The small air gap between the two surfaces constitutes a thin film whose thickness is zero at the point of contact and increases gradually toward the periphery.

- A monochromatic light beam is directed vertically onto this arrangement using a collimated source and a sheet of glass.

- The light reflects from both the upper and lower surfaces of the air film.

- The superposition of these reflected beams produces an interference pattern in the form of concentric rings.

- The patterns can be viewed through a microscope or on a screen.

The Reason for the Dark Centre

Although the thickness of the film at the centre is effectively zero, reflection from the lower surface (air–glass) introduces an additional phase shift of π radians, corresponding to a path difference of λ/2.

This causes destructive interference, resulting in a dark spot at the centre of the pattern.

The phase shift occurs because the lower reflection is from a denser medium (air → glass), while the upper reflection is from a rarer medium (glass → air), which does not produce a phase shift. Hence, their phase relationship leads to destructive interference at the centre.

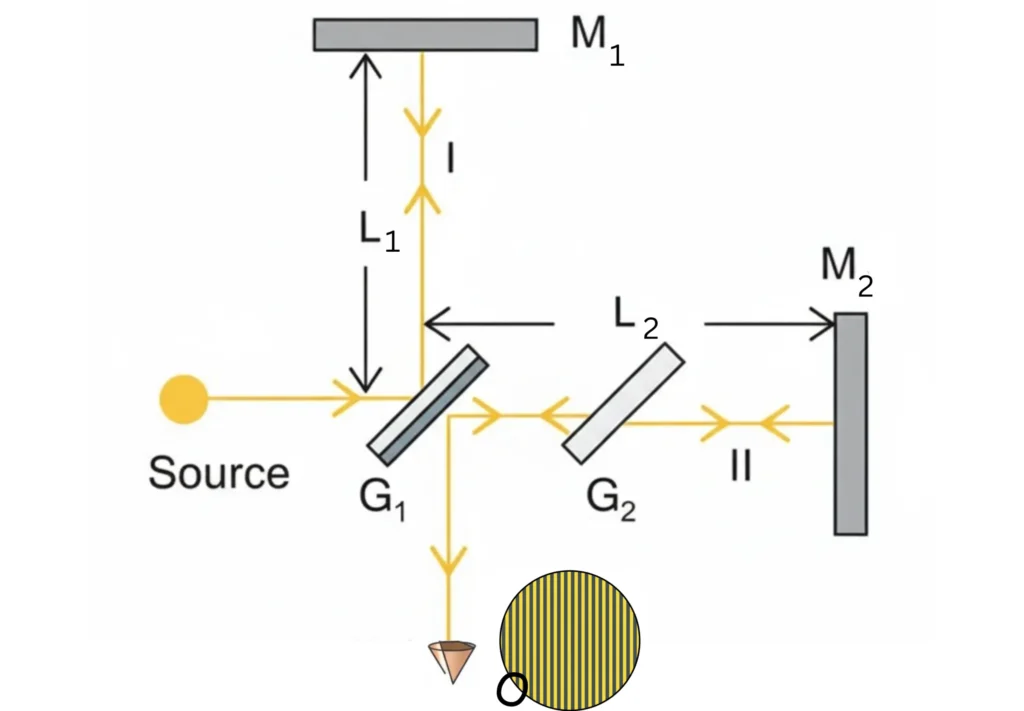

Michelson’s Interferometer

High-Precision Measurement

The Michelson Interferometer, devised by Albert A. Michelson in 1881, is a cornerstone instrument in optical physics. It employs the principle of light interference to measure:

- extremely small distances

- wavelength variations

- refractive index changes

… with remarkable precision.

Instrument Design and Function

- In its basic configuration, a beam of monochromatic light is directed toward a half-silvered plate (G₁), known as the beam splitter.

- The beam splitter reflects one part of the beam while transmitting the other, thereby producing two coherent light beams.

- One beam travels toward mirror M₁ via path L₁, while the other is transmitted toward mirror M₂ along path L₂.

- A compensator plate (G₂) of identical thickness to G₁ is placed in the path of the transmitted beam. It ensures that both beams traverse equal thicknesses of glass, maintaining coherence.

- After reflection from their respective mirrors, the two beams return to the beam splitter, where they recombine and interfere.

- The recombined light produces a pattern of parallel interference fringes, which can be observed directly or recorded with a detector.

Measuring Displacement

- One of the mirrors, typically

, is made movable, while

, is made movable, while  remains fixed.

remains fixed. - When

is displaced by a distance

is displaced by a distance  , the optical path difference between the two beams changes by

, the optical path difference between the two beams changes by  .

. - A shift in mirror position by

results in the movement of one complete fringe across the field of view.

results in the movement of one complete fringe across the field of view. - By counting the number of fringes (m) that pass as the mirror moves, the displacement can be determined with exceptional accuracy.

- The following relationship is used to measure the displacement:

![]()

- Because the smallest noticeable shift in the fringe pattern corresponds to a mirror displacement of

(which produces a path difference of

(which produces a path difference of  ).

). - This validates that the instrument can detect minute displacements on the order of nanometres.

Applications of Interference of Light in Modern Technology

1. High-Precision Measurement and Metrology

The Michelson Interferometer is fundamental in precision measurement and metrology.

Wavelength Determination

Interferometers accurately measure the wavelength (λ) of light sources. Michelson himself redefined the standard metre using the wavelength of red cadmium light. He showed that the standard metre was equivalent to 1,553,163.5 wavelengths of this light.

Distance Measurement

By counting fringe shifts (m) as the mirror moves, displacement (L) can be measured using.

![]()

For visible light, this yields nanometre-level precision (≈100 nm).

Calibration of Tools

In industries, it is employed for the calibration of machine tools and ultra-sensitive detection systems such as LIGO, which measures gravitational waves.

Surface Testing

In the optical manufacturing segment, it is used to assess the flatness or curvature of mirrors and lenses with sub-micrometre accuracy.

2. Thin Films in Optical Devices

Interference in thin films is used to control how much light is reflected, transmitted, or absorbed as colour.

High-Reflectivity (HR) Coatings

It involves stacking several thin layers to make mirrors that reflect almost all of the light.

Anti-Reflection (AR) Coatings

It is about adding thin layers to lenses to reduce reflections and let more light pass through.

Colour Filters

It consists of thin films that allow only certain colours of light to pass and is used in cameras and screens.

3. Holography

Holography is the method of producing 3-dimensional images that relies entirely on light interference.

- Recording: A laser beam is split into two beams, an object beam and a reference beam. The first lights up the object; the other goes straight to the recording plate. Their interference pattern stores the 3D information.

- Reconstruction: When the hologram is lit again with the reference beam, it recreates the original 3D image.

Holography and its modern cousins, light-field displays, volumetric projection, and digital holograms, are technologies in progress. They are slowly turning science fiction into everyday experience.

Conclusion

Interference was once observed merely as colourful patterns in soap bubbles or oil films. However, it now strengthens some of the most precise and transformative technologies in modern science and engineering. The phenomenon of light also validate the wave behaviour of light, as seen by different experimentation above.

Frequently Asked Questions

What do you know about the interference phenomena of light?

Interference of light is the phenomenon that occurs when two or more light waves superimpose at a point in space. This results in a redistribution of light intensity, i.e.;

- in phase waves → bright fringes → constructive interference

- out of phase waves → dark fringes → destructive interference

This phenomenon provides strong evidence for the wave nature of light.

What are the requisites for wave interference?

For interference to occur, the following conditions (requisites) must be satisfied:

- Coherent Sources

- Same Frequency (or Wavelength)

- Equal or Comparable Amplitudes

- Path Difference within Coherence Length

Write the difference between constructive interference and destructive interference of light.

| Aspect | Constructive Interference | Destructive Interference |

| Phase Difference | 0, 2π, 4π, … (even multiples of π) | π, 3π, 5π, … (odd multiples of π) |

| Path Difference | Integral multiple of wavelength | Odd half multiple of wavelength |

| Resultant Intensity | Maximum (bright fringe) | Minimum or zero (dark fringe) |

| Nature of Fringes | Bright bands | Dark bands |

Under what conditions do two or more sources of light behave as coherent sources?

Two or more light sources behave as coherent when:

- They have a constant phase difference.

- They emit light waves of the same frequency and wavelength.

- They are derived from a single parent source (e.g., in Young’s experiment, both slits are illuminated by the same monochromatic source).

How is the distance between interference fringes affected by the separation between the slits of Young’s experiment? Can fringes disappear?

In Young’s double-slit experiment, the fringe width ![]() is given by:

is given by:

![]()

Where,

wavelength of light

wavelength of light distance between the slits

distance between the slits distance of screen from the source of light (slits)

distance of screen from the source of light (slits) spacing between the two bright fringes

spacing between the two bright fringes

| Slit Separation | Fringe Spacing | Effect |

| ↑ | ↓ | Fringes get closer together. |

| ↑↑↑ | ↓↓↓ | Fringes may disappear due to loss of coherence. |

Can visible light produce interference fringes? Explain.

Yes, visible light can produce interference fringes.

In Young’s double-slit experiment, if monochromatic visible light (like from a laser or a filtered source) is used, distinct bright and dark fringes appear on the screen.

White light can also produce fringes, but they are coloured and less sharp, since different wavelengths interfere differently.

In Young’s experiment, one of the slits is covered with a blue filter and the other with a red filter. What would be the pattern of light intensity on the screen?

If one slit transmits blue light and the other red light, no regular pattern is observed because:

- The two lights have different wavelengths.

- Hence, they are not coherent and cannot interfere.

You would see two overlapping patterns of different colours, but no alternating bright and dark fringes.

Explain whether Young’s experiment is an experiment for studying interference or diffraction effects of light.

Young’s double-slit experiment is fundamentally an interference experiment. It demonstrates the superposition of light waves from two coherent sources.

However, each slit also acts as a source of diffraction, so the observed pattern is actually an interference pattern modulated by single-slit diffraction.

Thus, it is the primary effect, and diffraction modifies the pattern’s intensity distribution.

An oil film spreading over a wet footpath shows colours. Explain how it happened?

The colours observed in an oil film are due to the interference of light reflected from the upper and lower surfaces of the thin oil layer.

- Different wavelengths interfere constructively or destructively at different film thicknesses.

- As a result, different colours appear at different places — known as thin-film interference.

Could you obtain Newton’s rings with transmitted light? If yes, would the pattern be different from that obtained with reflected light?

Yes, Newton’s rings can be obtained with transmitted light as well as reflected light.

- In reflected light, the central spot is dark because of destructive interference.

- In transmitted light, the central spot is bright because the conditions for constructive and destructive interference are reversed.

Hence, the pattern is complementary — bright rings in reflection correspond to dark rings in transmission, and vice versa.