The Umayyads of Spain (Al-Andalus, 8th–15th Centuries), in a true sense, are the real benefactors of Europe and the West. Yet, they are barred from the 1000-year history of the West in the history curriculum.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Umayyads initially ruled the same region as the Abbasids, but the political landscape shifted due to rivalries and conflicts.

After the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate in Damascus (750), one surviving prince, Abd al-Rahman I, fled to the Iberian Peninsula (Spain). There, in Al-Andalus (Spain), he eventually established his stronghold and an independent empire.

Note, the land was conquered decades earlier by Tariq ibn Ziyad, a general under the Umayyad Caliphate of Damascus.

Umayyads of Spain (Al-Andalus, 8th–15th Centuries)

The new Umayyad state in Iberia turned Al-Andalus into one of the most advanced regions of the medieval world.

When the Umayyads ruled Spain, they built a civilisation of knowledge alongside political power. Córdoba, Granada, and Toledo became dazzling centres of learning. It was in these cities that Muslim, Christian, and Jewish scholars worked side by side.

This intellectual flourishing later sparked the European Renaissance.

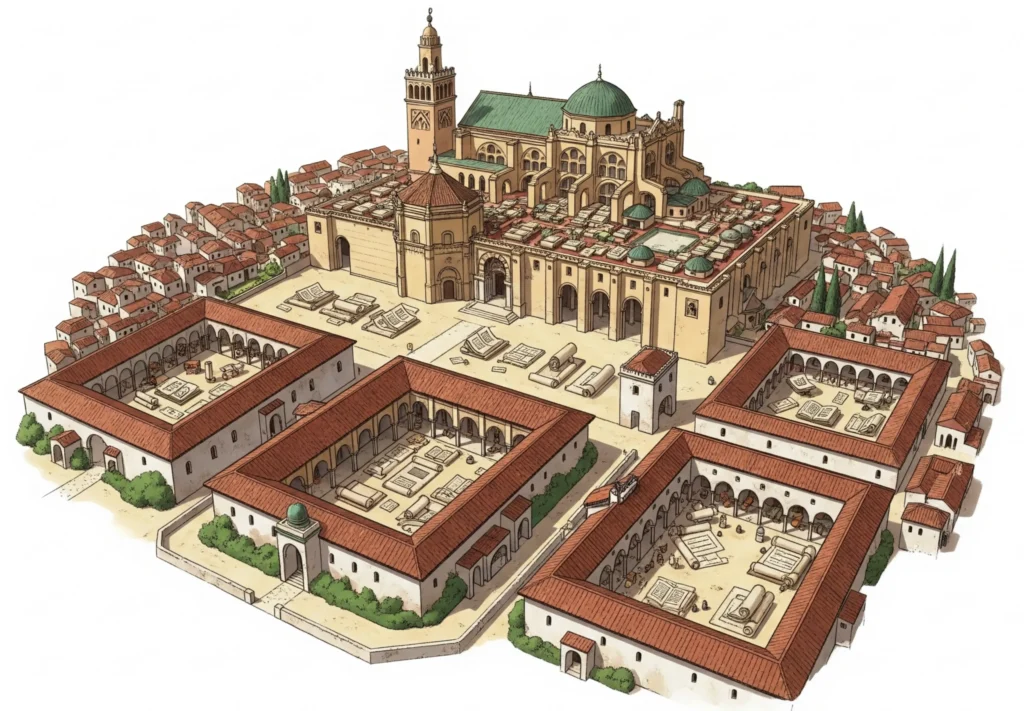

Córdoba | The City of Wisdom

Unlike the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, Córdoba itself functioned as a “House of Wisdom” for Al-Andalus. Its achievements included:

1. Libraries

The libraries of Al-Andalus once stood as the jewel of medieval Europe, unrivalled in their richness and scope.

Under Caliph Al-Ḥakam II (961–976), the royal library of Córdoba housed hundreds of thousands of manuscripts. They gathered it from Baghdad, Cairo, Damascus, and beyond. It was the largest library in Europe at the time.

Public and private libraries flourished across Granada, Seville, and Toledo, making Iberia a land where knowledge was as abundant as light.

At the same time, Christian Europe had only a handful of monastic libraries (usually fewer than a few hundred volumes each). In other words, Andalusian libraries were on another scale entirely.

According to George Makdisi and Maria Rosa Menocal, there were likely 70+ libraries in Al-Andalus by the 10th century. Some Andalusian chroniclers (like al-Maqqari) suggest there were dozens in Córdoba alone, not counting private collections.

2. Hospitals

The city had several hospitals (bīmāristāns) offering free treatment. They were simple yet quite advanced hospitals for their time. They had dedicated departments for surgery, ophthalmology, and even mental health.

3. Baths and Public Welfare

Córdoba contained over 300 public baths, paved streets, and oil lamps illuminating the city at night.

Contemporary Christian observers were stunned by its urban brilliance. Alvaro of Córdoba (9th century) complained that even Christians preferred mastering Arabic literature over Latin.

Later chroniclers contrasted the splendour of Córdoba with northern Europe. They noted that while Paris was still a village of huts, Córdoba had paved, lamp-lit streets, public baths, hospitals, and vast libraries.

4. Mosques and Schools

The Great Mosque of Córdoba was not only a place of worship but also a vibrant centre of scholarship, teaching Qur’ān, Hadith, law, philosophy, grammar, and sciences.

5. Scholarly Culture

Madrasa-like institutions and study circles flourished in Al-Andalus, attracting students and thinkers from across the Mediterranean world.

The Special Status of Córdoba

Córdoba was not just a political capital; it was an urban university, a place where knowledge, faith, and civic life flourished in harmony. Unlike other outsiders who used to come to a land, plunder its resources, and leave the land after achieving their goals, the Muslim Caliphate of Spain delivered.

The marks left by the Umayyad can still be seen all over the Iberian Peninsula, whether it is in their culture, language, or living styles. They (the Umayyads) created a civilisation and not just an empire to rule over.

One can easily say that under Abd al-Rahman II (822–852), Córdoba began to rise as a centre of learning, and later Al-Hakam II (961–976) expanded the institutions of the city and its royal library, attracting scholars from far and wide, causing The Birth of Intellectual Córdoba.

Notable Figures of the Umayyads

Damascus-based Umayyads (661–750)

| Name | Time Period | Religion | City of Activity (Primary) | Field(s) | Notable Work / Contribution |

| Ḥasan al-Baṣrī | 642–728 | Muslim | Basra | Theology, Asceticism | Early Islamic moralist; strong influence on Sufism |

| Khalid ibn Yazid (Umayyad prince) | d. 704 | Muslim | Damascus | Alchemy, Medicine | Commissioned translations of Greek works into Arabic; linked to early Islamic alchemy. |

| Al-Akhṭal (Ghiyāth ibn Ghawth) | 640–710 | Christian (Nestorian) | Damascus | Poetry | Court poet of the Umayyads; preserved Arab poetic traditions |

| Jarir ibn Atiyah | 650–728 | Muslim | Kufa/Damascus | Poetry | Famous Umayyad-era poet, known for satire and panegyrics |

| Al-Farazdaq (Hammam ibn Ghalib) | 641–728 | Muslim | Basra/Kufa | Poetry | Celebrated for panegyric poetry and poetic duels with Jarir |

Umayyads of Córdoba / Al-Andalus (756–1492)

| Name | Time Period | Religion | City of Activity (Primary) | Field(s) | Notable Work / Contribution |

| Abd al-Rahman II | r. 822–852 | Muslim | Córdoba | Patronage of arts & sciences | Made Córdoba a vibrant court of learning |

| Hasdai ibn Shaprut | 915–970 | Jewish (adviser to Caliph Abd al-Rahman III) | Córdoba | Medicine, Diplomacy | Physician, scholar, and patron of translations |

| Maslama al-Majriti | d. 1007 | Muslim | Córdoba | Astronomy, Mathematics, Chemistry | Introduced astronomical tables, contributed to arithmetic and alchemy |

| Al-Zahrawi (Abulcasis) | d. 1013 | Muslim | Córdoba | Medicine, Surgery (father of surgery) | Al-Tasrif (30-volume encyclopedia) |

| Ibn Hazm | 994–1064 | Muslim | Córdoba | Theology, Law, Philosophy, Literature | The Ring of the Dove |

| Ibn Bajja (Avempace) | d. 1138 | Muslim | Zaragoza | Philosophy, Medicine | Tadbīr al-Mutawaḥḥid |

| Ibn Tufayl | c. 1105–1185 | Muslim | Granada | Philosophy, Medicine | Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān |

| Ibn Rushd (Averroes) | 1126–1198 | Muslim | Córdoba, Seville | Philosophy, Medicine, Law | Kitab al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb (Generalities of Medicine) |

| Al-Ghafiqi | d. 1165 | Muslim | Córdoba | Medicine (Ophthalmology) | Wrote on diseases of the eye; a pioneer in optics and surgery |

| Al-Sarafi & translators in Toledo | 12th c. | Christian (working with Muslims & Jews) | Toledo (After Reconquista) | Translation Movement | Translated Arabic works (Averroes, Avicenna, Al-Zahrawi) into Latin |

| Ibn al-Baytar | d. 1248 | Muslim | Málaga, Granada | Pharmacology, Botany (catalogued 1,400 plants) | Compendium of Simple Medicaments and Foods |

| Ibn al-Khatib | 1313–1374 | Muslim | Granada | History, Literature, Medicine (early notes on contagion in plague) | Kitab al-Ihata fi Akhbar Gharnata (History of Granada) |

| Ibn Khaldun (Granada period) | 1332–1406 | Muslim | Granada (briefly), later Tunis & Cairo | Philosophy, History, Sociology (foundations of sociology & historiography) | Muqaddimah (Prolegomena) |

| Ibn Zamrak | 1333–1393 | Muslim | Granada | Poetry, Politics | Court poet of the Alhambra; inscriptions on its walls are his verses |

The Legacy of Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was not a local marvel; it was a global pivot. From the libraries of Córdoba to the classrooms of Oxford, Islamic Spain ignited the Renaissance. Its scholars showed that civilisations flourish when faith and reason walk together.

The works of Andalusian thinkers were translated into Latin at Toledo and spread across Europe, nourishing the roots of scholasticism, philosophy, and eventually the Renaissance.

The Fall of Al-Andalus

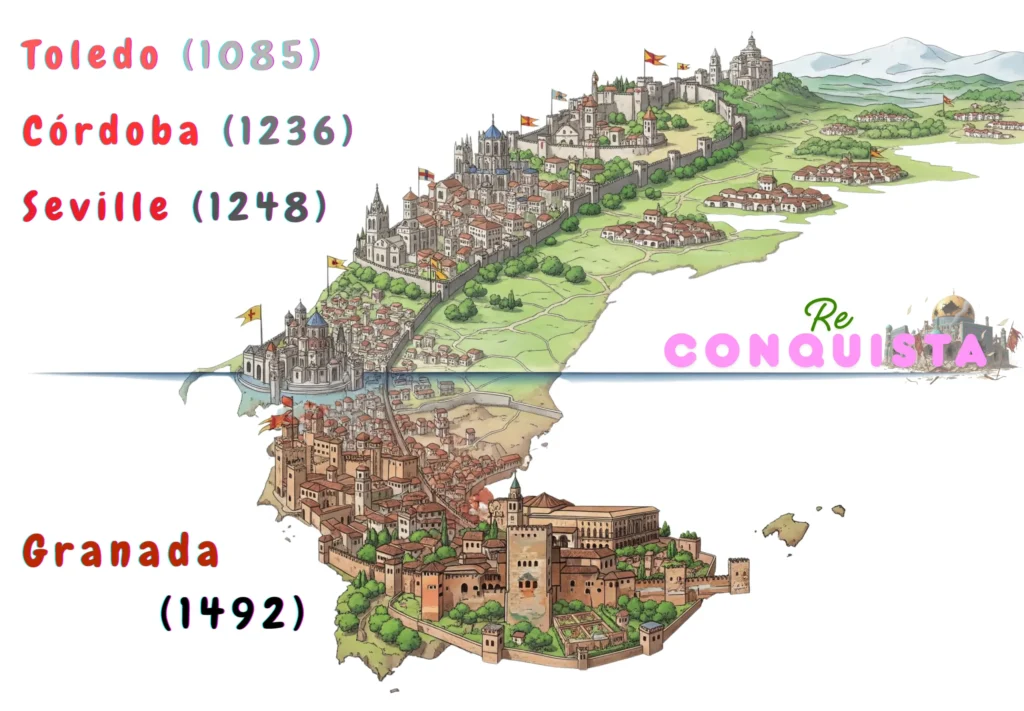

The Reconquista was the centuries-long process (roughly 8th–15th centuries) in which the Christian kingdoms of northern Spain and Portugal gradually expanded southward, reclaiming territory from Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula.

The Reconquista began soon after 711, when Muslim forces first conquered most of Iberia, and small Christian redoubts in the north (Asturias, León, Navarre, Aragón, later Castile and Portugal) resisted.

The turning points came step by step:

- Toledo fell in 1085, opening a gateway for translations into Latin.

- Córdoba, once the “City of Wisdom,” fell in 1236.

- Seville followed in 1248.

- Finally, Granada, the last Muslim stronghold, surrendered in 1492.

Bib-Rambla Square | The Burning of Knowledge

The Reconquista alone did not end the Andalusian civilisation. What truly dimmed its light was the deliberate erasure of its intellectual treasures. With the Reconquista came suspicion, hostility, and ultimately destruction.

The most devastating moment came under Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros in 1499. Tens of thousands of Arabic manuscripts in Granada were confiscated. In the Bib-Rambla square, in front of crowds, cartloads of books were heaped and set ablaze.

A few medical and scientific works were quietly spared for translation into Latin — valued for their “usefulness.” But everything else was condemned as heretical and consumed by flames — including:

- Qur’anic Commentaries

- Philosophy

- Literature

- History

- Poetry

This was the single largest book burning in European history.

The once-great constellation of libraries:

- Córdoba’s cosmic royal library

- Granada’s private collections

- Toledo’s storehouses

- Seville’s archives

… were reduced to ash. What survived was fragmentary, often preserved only in translation outside Iberia.

Conclusion

Not Only the Sword but Also the Pen

Instead of simply conquering Iberia and plundering it, the Umayyads of Spain cultivated it into one of the most enlightened regions of the medieval world.

Unlike many empires that thrived on plunder, the Umayyads built enduring institutions. They built hospitals, universities, libraries, and urban infrastructure that transformed Al-Andalus into a beacon of knowledge in Europe.

Its hospitals treated patients free of charge at a time when most of Europe had no such system. Its streets were paved and lamp-lit when Paris was still a village of huts. Its libraries held more books than all the monasteries of Christendom combined, making Córdoba the intellectual capital of Europe.

Although much of this treasure was tragically lost to flames during the Reconquista, the brilliance of Al-Andalus continues to illuminate history. It reminds us that civilisations reach greatness not merely through power, but through knowledge, coexistence, and the nurturing of human potential.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Who were the Umayyads of Spain (Al-Andalus)?

The Umayyads of Spain – the real benefactor of Europe and the West – were a Muslim dynasty that ruled Iberia from the 8th to the 15th century, creating one of the most advanced and culturally rich societies in medieval Europe.

Why was Córdoba called the “City of Wisdom”?

Córdoba became a global centre of learning, boasting vast libraries, hospitals, schools, and paved, lamp-lit streets when much of Europe was still in the Dark Ages.

What contributions did Al-Andalus make to Europe?

Al-Andalus preserved and expanded Greek, Roman, and Islamic knowledge in science, medicine, philosophy, and mathematics. These works later fuelled the European Renaissance.

What happened to the libraries of Al-Andalus?

After the Christian Reconquista, tens of thousands of manuscripts were burned in public squares, especially in Granada in 1499, leading to the loss of priceless intellectual heritage.

How does Al-Andalus remain relevant today?

Its legacy of knowledge-sharing, religious coexistence, free healthcare, advanced urban life, and vast learning institutions shows the power of cultural exchange in shaping global civilisation.